Click on the links below to see images from the successful operation to capture Puntung and transport her to her new home.

Click on the links below to see images from the successful operation to capture Puntung and transport her to her new home.

What will it take to save the Sumatran Rhino

-

Now or never: what will it take to save the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis from extinction?

-Abdul Wahab Ahmad Zafir, Junaidi Payne, Azlan Mohamed, Ching Fong Lau, Dionysius Shankar Kumar Sharma, Raymond Alfred, Amirtharaj Christy Williams, Senthival Nathan, Widodos Ramono and Gopalasamy Reuben Clements.

Copyright notice: Cambridge University Press

Read the full article.

We’re sure many of you know that one of the world’s most magnificent and docile creatures, the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), is in deep trouble.

But just how bad is it? From a population of around 320 estimated in 1995, experts now say it could be down to as low as 216 individuals.

One of Rimba’s researchers, Reuben, was involved in a review published recently in the international journal Oryx. This paper was led by Ahmad Zafir Abdul Wahab (currently doing his PhD based at Universiti Sains Malaysia; ahmad.zafir@gmail.com) to find out what needs to be done to save this species from extinction. The consensus is that:

1) Wild individuals have to be captured and put in carefully managed forests that are as large and natural as possible.

2) There has to be an urgent injection of government and private funding to improve protection and monitoring capacities of agencies working on rhino conservation in four priority areas: Bukit Barisan Selatan and Way Kambas National Parks in Sumatra, and Danum Valley Conservation Area and Tabin Wildlife Reserve in Sabah.

Once this basic level of funding is secured for these priority areas, more funds need to be channeled towards a search party to determine the status of rhinos in two other important areas, Gunung Leuser in Sumatra and Taman Negara in Peninsular Malaysia.

Just how much are we talking about for this basic level of funding? Only USD1.2 million! Pocket change for some people, especially the guy who bought a 1939 Batman comic for the same price at an auction in Dallas, back in February 2010.

Surely the price of the Sumatran rhino’s existence is worth much more than a comic book? Surely governments and noble companies can put together a fraction of their GDPs and annual revenues to save this species?

Although the Sumatran rhino has a negative SAFE index of -1.36 and is tipping over into the chasm of extinction, there have been positive historical examples of rebounding rhino populations:

In southern Africa, white rhinos (Ceratotherium simum) rebounded from just 20-50 individuals in the early 1900s to around 17,480 individuals today.

In India and Nepal, Indian rhinos (Rhinoceros unicornis) rebounded from only 200 individuals at the turn of the 20th century to around 2,575 individuals today.

Recovering from 216 individuals is by no means easy in this day and age, but history has shown it’s possible.

Please contact organizations actively engaged in Sumatran rhino conservation like the Borneo Rhino Alliance or International Rhino Foundation if you want to help preserve the existence of the Sumatran rhino. It’s now or never…

Full citation: Ahmad Zafir, A. W., Azlan, M., Lau, C. F., Sharma, D. S. K., Payne, J., Alfred, R., Williams, A. C., Nathan, S., Ramono, W. S., and Clements, R.G. 2011. Now or never: what will it take to save the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) from extinction? ORYX 45: 225-233.

Why are Sumatran rhinos so seriously endangered?

Current situation

The current number of living individuals of the Bornean subspecies of the Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni; also known as the Bornean rhino) is possibly around forty or less. Sabah now offers the only likely prospect for saving this sub-species, and the best prospect for saving the species in Malaysia.

Based on morphological characters, Groves (1965) favoured separation of the Borneo form of the Asian two-horned or Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) as a distinct sub-species (D. r. harrissoni), with D. r. sumatrensis regarded as a single form occurring in Sumatra and Peninsula Malaysia. Based on mitochondrial DNA, however, Amato et al (1995) concluded that all Sumatran rhinos in Indonesia and Malaysia should be regarded as a single conservation unit. These results are of great significance : the Sumatran rhinoceros is now so highly endangered that mixing of Bornean and Sumatran forms in captive situations represents a potentially significant means to increase the number of births.

Historical context

The fact that the ecologically similar Javan rhino and Malay tapir became extinct in Borneo before the expansion of the human population suggests that natural factors may have played a role in the low population density of rhinos. Pressure from hunting of rhinos for their horns (a mainstay of ancient Chinese medicine) has likely been ongoing over long periods. The Bornean rhino was widely distributed in at least some localities in eastern and central Sabah in the late nineteenth century (Payne 1990), but the population was likely depleted below natural carrying capacity by that time. The species was already regarded as very rare and endangered in Sabah by 1961 (Burgess, 1961). Payne (1990) showed that isolated ones or twos of rhinos occurred in many parts of eastern Sabah as recently as the 1970s, but the species quickly became extinct at most sites during the 1980s. Davies and Payne (1982) noted that all Sabah rhino records compiled in 1981 showed that a natural salt source or mud volcano was present within a maximum of 14 km for all records, suggesting that the species distribution may be limited by access to certain minerals. More recently, it has been noted that all confirmed Sabah rhino records from late nineteenth century to present occur on sedimentary (most) and volcanic (some) derived soils, with none on crystalline basement and ultramafic rocks. Although overall rhino numbers have continued to decline in Sabah since 1980, the general pattern of rhino distribution (very small breeding populations in what are now Tabin Wildlife Reserve and Danum Valley Conservation Area, with a few scattered individuals elsewhere) has remained remarkably constant.

The argument that it is too late to save this rhino because of inbreeding is not valid. The African and Indian rhinos species were in a similar situation about a century ago, as were several other large mammal species such as the European bison, Arabian oryx and Pere David’s deer, all of which were built up to much larger numbers with appropriate passion and action by a small number of people.

Major threats faced by rhinoceros today

Very low numbers

The Sumatran rhino is one of the most endangered animal species anywhere in the world. Less than 40 rhinos are believed to survive in Sabah. Even if half are females, and some are too old or too young to reproduce, perhaps only six to seven remaining rhinos have the potential to give birth. With a birth interval of three years under optimum conditions, no more than two rhinos are being born annually (see below). The Allee effect (Allee, 1931) refers to a phenomenon whereby a positive correlation exists between of individual fitness (e.g. survival probability, fertility, reproductive rate) and population density of the species (Courchamp et al, 2008). As numbers of individuals of a species decline to a low very level, the various factors associated with very low numbers (e.g. narrow genetic base, locally skewed sex ratio, difficulty in finding a fertile mate, reproductive pathology associated with long non-reproductive periods; see below) conspire to drive numbers even lower, to the extent that death rate eventually exceeds birth rate, even with adequate habitat and zero poaching. In the absence of specific actions to bring Sumatran rhinos together and boost production of offspring, therefore, there is a strong possibility that the Sumatran rhino may go extinct even if protection of rhino habitats and rhinos can be maintained and improved.

Birth rate

The only information on inter-birth interval for the Sumatran rhino comes from Cincinati Zoo, where three young were born at intervals of 2 years and ten months between 2001 and 2007. For wild Sumatran rhinos, actual birth interval is likely to have been less in recent decades, because of the paucity of sites with fertile females and males present.

Cranbrook (2009) points to the long inter-birth interval of these taxa, and refers to Johnson’s (2006) modeling of different levels of off-take applied to large mammals, whereby a small increase in juvenile mortality can hold recruitment rates below a level needed to replace breeding adults. If Danum and Tabin are each assumed to contain 15 rhinos, and that about half are females, and that of those females some are too old or too young to reproduce, perhaps only three or four rhinos in each area will be reproductively active. With a birth interval of three years under optimum conditions, only one rhino will be born into each population annually – this would explain the apparent zero rate of population increase in these protected areas. Even this may now represent an optimistic scenario.

Reproductive tract pathology

At least half the female rhinos caught between 1984 and 1995 had reproductive tract pathology (Schaffer, 2001), a phenomenon associated with lack of breeding and carrying of fetuses to successful birth that appears to particularly afflict rhinos (Hermes et. al, 2006). The fact that at least some wild female Sumatran rhinos have exhibited this pathology at time of capture indicates that not all wild female rhinos are breeding, presumably due to insufficient fertile males to meet and mate.

Skewed sex ratio

A period of active capture of rhinos from sites in Sumatra in 1959, and from Sumatra, Peninsula Malaysia and Sabah where forest was being converted to plantations between 1984 and 1995 and Sabah revealed differences in sex ratio. Of nine rhinos caught in the Siak River area, Riau, Sumatra, in 1959, only one was a male (Skafte, 1964). At that time, Riau was largely forest-covered. Of twenty rhinos caught at various locations in Sumatra between 1985 and 1992, a period of accelerating forest loss, eleven were females. Later, in September 2005, two immature female rhinos were caught (named Rosa and Ratu), each having apparently moved into inhabited semi-forest areas from Bukit Barisan Selatan and Way Kambas National Park respectively. Of twelve rhinos caught in Peninsular Malaysia between 1984 and 1994 from several separate regions, nine were females. Since female Sumatran rhinos are believed to have smaller home ranges than males, and siting of rhino traps was based on well-used rhino paths, and the sample size is small, this bias towards females is not unexpected. Yet a severe bias in sex ratio in the opposite direction was observed in Sabah where, between March 1987 and November 1995, a total of ten rhinos were captured. Of those, nine were caught within an area of about 120,000 hectares which would up to around 1980 have been contiguous forest cover. Of the nine, one was a mature female and eight were mature males. Although the sample size is small by normal standards in biology, there are unlikely to have been many, if any, rhinos not located during the conversion of 120,000 ha of forest. Thus, the remnant rhinos in this small population were almost all mature males. The tenth rhino, caught in April 1989, was a young female (named Lun Parai) that had arrived near a major road and which may have come from Tabin Wildlife Reserve, the nearest large block of forest some 25 km away in a straight line. Not much can be gleaned from these records and a similar situation will not happen again, as there is now much less forest and much fewer rhinos. It is clear, however, that a biased sex ration may occur in very small populations of Sumatran rhino. The observations from Sabah also suggest that female rhinos, potentially easier to locate than males because of their presumed use of smaller areas, had already been selectively taken by hunters before the start of government-sponsored trapping for a captive breeding programme. Also, despite the very small sample size, the three cases of young rhinos moving out of forest into areas inhabited by humans suggests that young adult rhinos may tend to move far from their natal area.

Hunting and trapping

At any time, a single rhino poaching or inadvertent trapping event may represent the tipping point that pushes the species to a trajectory of extinction in Sabah.

Cause for optimism

The rhino in Sabah represents one of the few examples of a tropical large mammal where forest loss is not a major issue threatening the species. Conservation efforts can focus, therefore, exclusively on minimizing human-induced mortality and on bringing fertile females and males together.

References

Allee, W C 1931 Animal Aggregations. A study in General Sociology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Amato, G., D. Wharton, Z.Z. Zainuddin and J.R. Powell. 1995. Assessment of conservation units

for the Sumatran rhinoceros. Zoo Biology 14: 395-402.

Burgess, P F 1961. Wildlife Conservation in North Borneo. Malay Nat. J. 21st Anniversary Edition. Pp.143-151.

Courchamp, F, Berek, L & Gascoigne, J 2008 Allee effects in ecology and conservation. Oxford University Press, UK

Cranbrook, E. of 2009. Late quaternary turnover of mammals in Borneo: the zooarchaeological record. Biodiversity and Conservation 1572-9710 (Online), Springer Netherlands.

Davies, A G & Payne, J 1982 A Faunal Survey of Sabah. WWF-Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Groves, C P 1965 Description of a new subspecies of rhinoceros, from Borneo. Saugetierkundliche Mitteilungen 13 (3): 128–131

Hermes, R., T. B. Hildebrandt, C. Walzer, F. Göritz, M. L. Patton, S. Silinski, M. J.

Anderson, C. E. Reid, G. Wibbelt, K. Tomasova and F. Schwarzenberger. 2006. The

effect of long non-reproductive periods on the genital health in captive female white

rhinoceroses (Ceratotherium simum simum and C. s. cottoni). Theriogenology 65: 1492-

1515.

Payne, J 1990 The distribution and status of the Asian two-homed rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni) in Sabah Malaysia. Project 3935. World Wildlife Fund-Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Schaffer, N 2001 Utero-Ovarian Pathological Complex of the Sumatran Rhinoceros

(Dicrerorhinus sumatrensis). (Pages 76-77 in : Schwamnler, H, Foose, T, Fouraker, M and Olson, D, Recent Research Elephants and Rhinos. Abstracts of the International Elephant and Rhino Research Symposium, Vienna, June 7-1 1, 2001)

Skafte, H 1964 Rhino Country. London: Hale.

Borneo’s hairy rhino

Together with the Javan Rhino, the Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) is the most critically endangered of the rhino species. This rhino species may represent the rainforest relic of a rhino which was once adapted to the open woodlands of the Pleistocene ice ages when sea levels were much lower than now, and Borneo and Sumatra were joined to mainland Asia via savannahs now under the South China Sea.

Over the past millennium, hunting and habitat loss have driven this rhino to the brink of extinction. Now, there may be just too few fertile females and males in any one forest area to sustain breeding.

Scientists now estimate that there are only about 200 animals remaining in the wild, clinging to existence in highly fragmented populations. As the persistence of populations in Peninsular Malaysia is very much in doubt, Indonesia and Sabah hold the only significant breeding populations. Between 30 – 40 rhinos are thought to be found in Sabah’s Tabin Wildlife Reserve, Danum Valley Conservation Area, and pockets of eastern and central Sabah.

In Indonesia, small populations may be found in three Indonesian National Parks in Sumatra: Bukit Barisan Selatan, Way Kambas and possibly Gunung Leuser.

Sumatran rhinos can be expected to persist and breed only in protected areas where they are physically guarded from harm by Rhino Protection Units. The continuation of this protection provides a necessary but perhaps insufficient means for the species’ survival. Active programmes to bring fertile females and males together may now be a necessary supplement to pull the species back from the brink of extinction.

The Littlest rhino

The Sumatran Rhino found in Sabah, is somewhat smaller than that found in Sumatra. It ranges from 4 to 5 feet in height, and 6.5 to 9.5 feet in length. Of course little is relative when discussing rhinos! Sumatran rhinos still weigh in at between 500 and 800 kilos. The Borneo form has been classified as a sub-species belonging to the same species as the rhinos found in Sumatra. This is based on skull shape, DNA and a slight difference in size – the Sumatran rhinoceros is now known as Dicerorhinus sumatrensis sumatrensis while the Bornean rhinoceros is more correctly referred to as Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni.

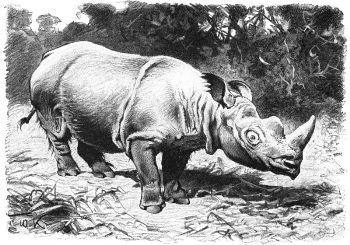

The Sumatran Rhino is also known as the Asian Two-horned rhino because of its two horns – a larger anterior horn and a smaller horn behind it. However, the main feature that distinguishes it from the other four rhino species is its covering of hair and reddish-brown skin. This is why the Sumatran rhino is sometimes called the ‘hairy rhino’.

Sumatran rhinos are browsers and consume a wide variety of plant species in the tropical forest. They have a lifespan of between 25 and 35 years. Mothers give birth to one calf every 3 years and the gestation period for a Sumatran rhino is 15-16 months. Females reach sexual maturity between 6 and 7 years of age, while males mature at approximately 8 years of age. Sumatran rhinos are generally solitary in nature and generally form temporary associations for mating before parting ways once again.

Meeting Tam in Borneo: our last chance to save Asia’s two horned rhino

Face-to-face with what may be the last of the world’s smallest rhino, the Bornean rhinoceros.

Nothing can really prepare a person for coming face-to-face with what may be the last of a species.

I had known for a week that I would be fortunate enough to meet Tam. I’d heard stories of his gentle demeanor, discussed his current situation with experts, and read everything I could find about this surprising individual. But still, walking up to the pen where Tam stood contentedly pulling leaves from the hands of a local ranger, hearing him snort and whistle, watching as he rattled the bars with his blunted horn, I felt like I was walking into a place I wasn’t meant to be. As though I was treading on his, Tam’s space: entering into a cool deep forest where mud wallows and shadows still linger. This was Tam’s world, or at least it should be.

A living—still surviving—Bornean rhinoceros, Tam is only one of an estimated forty left in the world, maybe less. At 620 kilograms (1430 pounds), Tam is a full grown male rhino. Researchers have estimated his age to be about twenty with at least another decade before him. Surprisingly pinkish in color, he is sparsely covered by large black hairs, while both of his two horns—unlike other Asian rhinos who only sport one—have been rubbed dull against the walls of his pen.

Tam is a survivor—that is certain. He survived his forest habitat being whittled into smaller and smaller pockets. He survived his right foot being caught in a poacher’s snare leaving an inch-wide white scar circling his ankle. And he had survived when he wandered directly into an oil palm plantation in early August of last year, probably propelled by his injury. He had beaten the odds, this one.

Everything has changed for Tam now. Cynthia Ong, Director of Land Empowerment Animals and People (LEAP) which has worked on raising funds to save the Bornean rhino, said that since wandering into a plantation over a year ago Tam had become “very manja”. Not being Malaysian I didn’t know the word, but she assured me every Malaysian mother’s daughter knew it, and it meant something like ‘lovingly spoiled’.

It’s true that Tam has entered a kind of retirement. Instead of being butchered for his horn—a fate suffered by a female Bornean rhino in 2001—Tam was immediately seen as a symbol of a dying, but not yet dead, species. His surprising arrival on an oil palm plantation brought the government and conservation community of Sabah into action. He now has a 2.5 hectare pen to his own, complete with forest cover and two mud wallows; he is fed a selection of greens gathered every morning and afternoon by rangers with the Sabah Wildlife Department; and he is protected 24-7 by an anti-poaching squad.

Of course, the situation is not perfect, it would be best if Tam could have remained in the wild to live out his life—only this time near other rhinos, instead of the forest patch where he was trapped and alone. But his injured foot had required care and now he is too accustomed to humans to simply be placed back in the wild, because he would likely wander into human habitations again—where he may not be so lucky.

However his appearance on the human stage has given Tam another role to play: a survivor’s role.

Tam—this massive, purplish, very ‘manja’ animal who almost crushed my hand against the bars as I tried to take rapid photos into his pen because he probably thought I was trying to feed him the camera—could be the key to bringing the Bornean rhino back from the brink.

The story of the two-horned Asian rhino

The story of Tam and his kind goes back—way back.

Bornean rhinos are actually a subspecies of the Sumatran rhino, of which there are only an estimated 250 left in the world. Sumatran rhinos—and their Bornean subspecies—are the only rhinos left in the genus, Dicerorhinus. Most researchers believe that the Sumatran rhino is the last living representative of early Miocene rhinos and therefore the oldest rhino species left in the world, one that emerged between 15 and 20 million years ago.

This also makes the Sumatran rhino the closest living relative to the legendary Woolly rhinoceros, which roamed the steppes during the Ice Age. Evidence of their ancient ancestry is seen in the Sumatran rhinos’ thick black strands of hair; the same hair that probably covered the Woolly rhinoceros, only in a far thicker coat.

For millions of years the Sumatran rhino inhabited Southeast Asia, from Borneo to Northeastern India. Living largely solitary lives, they preferred deep tropical forests near muddy and swampy areas. Not known to fight over territory, the Sumatran rhino is actually quite a gentle creature, despite its heavy bulk and huge horns. Considered the most vocal of all the rhinos, it makes a number of surprising noises, including one which has been compared to a whale singing.

After millions of years the rhino’s fate turned. Following the path similar to many lost and threatened species in the region, habitat loss and large-scale hunting drove the rhino into smaller and smaller pockets until it finally reached its current pathetic state. The rhino’s horn is key to understanding the demise of the animal; it fetches hefty prices (upwards of 30,000 US dollars per kilo) on the black market where it is sold as traditional Chinese medicine. Despite decades of anti-poaching measures and laws, the trade is still booming and rhinos across the world are still paying the price. In fact this year has been a particularly bad one for rhinos worldwide: poaching is at a fifteen-year-high and rhino horn by kilo is not worth more than gold.

The Sumatran rhino has already lost one subspecies to extinction—the Northern Sumatran rhino, once prevalent in India, Burma, and Bangladesh—while the remaining two subspecies—the Bornean and the Western Sumatran rhino—hang-on by a thread in Borneo, Sumatra, and peninsular Malaysia.

On top of all of this Junaidi Payne, chairman of the Borneo Rhinoceros Alliance (BORA) and longtime conservationist with WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature), Malaysia, says that a new and insidious threat faces the species: population collapse.

“In the past, rhinos were threatened by poaching, loss of habitat and so on. But now they are mostly threatened by the simple fact that there just aren’t enough of them around in one place anymore,” Payne told The Star.

Habitat is so fragmented and rhino numbers so low, that many remaining rhinos are simply unable to locate another individual to breed with. They are caught in pockets of forest surrounded by oil palm plantations with no opportunity to safely cross the plantations and reach other rhinos. Tam is an example of this: his front foreleg was caught in a snare that was mostly likely put out by oil palm plantation workers.

“Most workers in oil palm plantations, as well as rural people in general, do not earn big incomes and survive how they can” says Payne. Palm oil plantation workers—mostly immigrants from Indonesia and the Philippines in Sabah—as well as local people in some areas, are known to set snares to catch deer and other animals for meat, but these snares trap indiscriminately and sometimes injure or kill Bornean elephants, sunbears, rhinos, and other imperiled species.

But it’s not just the situation on the ground that has brought the Sumatran rhino so close to extinction; it is also a matter of perception. Both Payne and Ong told me that Tam and his kind have been largely overlooked by the public, both local and international.

“People don’t understand the significance of the rhino,” Ong says, who describes the Sumatran rhino as “one of the top five endangered mammals in the world”. Ong adds that the public simply doesn’t realize how rare the Sumatran rhino is or its evolutionary importance as the last representative of an ancient mammal line.

In Sabah most of the focus is on orangutans with elephants coming a distant second. When compared to the huge amount of information available on orangutans, there are few research papers, books, and no documentary films on Sumatran rhinos. Any conservationist knows that it is difficult to save a species that doesn’t excite the imagination of the public, and since rhinos are so secretive and rare they have largely been out of sight, out of mind.

“It could be an intimate relationship [between humans and rhinos], but how we choose to engage shows us where we are at as a human community,” Ong says.

The good news is that the Sumatran rhino has a new champion. Having worked to save numerous species in Sabah, Payne says that he has now dedicated his time to saving the embattled rhino.

However, his decision raises some eyebrows.

Why work to save a doomed species?

Why? Junaidi Payne gets asked this question all the time. Why work to save a species that is doomed to extinction? Why not work on a species with a little more promise, like, say, the orangutan or elephant?

“Simple reason,” Payne told me. “There are estimated to be 11,000 orangutans [in Sabah alone] and probably 1,500 [Bornean pygmy] elephants, but there are no more than forty rhinos and new populations have stagnated and are going down slowly. It’s about need.”

However, Payne is not shy about the difficulties facing him and others who have joined the new effort to save the Bornean rhino.

“One can guess that there might be only 6-7 fertile females [of Bornean rhinos] in existence,” he says, adding that with this knowledge in hand “anyone, any common sense person, would agree that [attempting to save the subspecies] is a waste of time”.

I asked Payne if he believed then that the rhino was doomed.

“Probably,” he answered. “Yet maybe not”. And it is that ‘maybe not’ that really interests and excites Payne. He remains hopeful—and with good reason.

Payne pointed out to me that past conservation success stories prove the rhino is not a lost cause. At the end of the Nineteenth Century, Africa’s white rhinoceros—once widespread—were down to just over twenty individuals surviving in one location in South Africa. Intensive conservation measures pulled the white rhino back from the brink: today an estimated 17,480 white rhinos live in east and southern Africa, making it the most populous rhino species in the world.

But it’s not just the white rhino: over one thousand European bison survive today, all of which are descended from just a dozen individuals in captivity; and after going extinct in the wild in the 1970s, the Arabian oryx has been successfully reintroduced into its native habitat—several hundred strong—while at least 6,000 survive in captivity.

Despite these and other success stories, Payne says that there has been a “strange change where academics claim [species] are doomed unless you have a certain minimum number of individuals – often the number 500 has been proposed “.

Payne calls this the “geneticist’s tyranny” where in spite of “empirical evidence” that large mammals have gone through genetic bottlenecks and come back, many geneticists would claim that the fate of the rhino is already decided.

“People are forced to give reasons why we save these species,” Ong added, but it’s clear that “you can change the course of events”.

Of course, the question of ‘why?’ could be asked of any endangered animal. Why put money, time, and energy into saving a species at all? Certainly, species provide what are called ‘ecosystem services’, they in concert with their environment, provide pollination, clean water, clean air, food, medicine etc. But are there other reasons?

“I can only say—I’m shy to say it […] but the general answer would be that humans, having even thought about [saving a species], gives some responsibility to actually save them,” Payne said.

Ong agrees that the decision to save a species says just as much about humans as it does about the embattled and vanishing species: “I see this as a question of where we are in our evolution and how do we respond to this critical situation.”

She then puts it in more personal term: “When our great grand children ask ‘when you found out about [the rhino] what did you do?’ How will we respond?”

The plan going forward

Of course, it’s not enough to simply decide to save a species on the precipice of extinction, large-scale action and a lot of funds are required. In the case of Sumatran rhinos, there has already been a concerted effort to save the species—which ended in failure.

The Sumatran rhino is the world’s smallest rhino species, while the Bornean subspecies is smaller than the Western Sumatran. Photo by: Jeremy Hance.

In 1984 the IUCN brought together a wide range of interested parties from Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah, Indonesia, the United States, and Britain to discuss how to save the Sumatran rhino. They decided the best thing would be a globally managed program of captured individuals for breeding in captivity in a number of different locations. Between 1986 to1994, around forty Sumatrans rhinos were caught and placed in zoos, as well as other closely managed situations.

The government of Sabah embraced the plan. In 1988 they established Sabah Wildlife Department, previously a division of the Forestry Department, which was created in part as a means to facilitate rhino conservation.

Unfortunately the well-thought out plan didn’t produce: only one breeding pair was successfully established in Cincinnati Zoo, bearing three offspring. Nearly all the original rhinos caught are now dead; the only female to bear offspring died just this year.

Starting in the late 1990s, another breeding site of 100 hectares was established at Way Kambas on Sumatra. However, while the conservation center includes three females and two males, no offspring have been born. Conservationists hope that will change, since the second male was only brought in two years ago.

“The thinking is that the whole idea of very closely managed rhinos in captivity isn’t working as well or as fast as is needed to save the species,” Payne says.

In 2007 researchers concluded at a Conference on Rhino Conservation in Sabah that due to reproductive issues and possible inbreeding, rhino numbers in the Malaysian state had stagnated and were probably declining, therefore simply preserving habitat for rhinos would not save them, nor they thought would captivity. A bold and innovative proposal was put forth.

As Payne tells it, the conservation community was confronted with a choice: either do nothing or place rhinos in a large conservation area that would be less closely managed.

Two years later Payne and BORA are in the midst of assisting the Sabah Wildlife Department in implementing a vast fenced-in sanctuary—4,500 hectares—where Bornean rhinos can be brought together. The rhinos will be monitored, but will have “minimal human influences”. They will be largely left alone in the hopes that nature will take its course and the rhinos will breed.

“In theory we are putting one half of Sabah’s rhino eggs in one basket,” Payne says of the plan.

Ong adds that conservationists have to “make a decision to go all the way with human intervention or why bother.”

Only rhinos which are cut off from others will be placed in the new sanctuary. Rhinos in parks like Tabin or Danum, which are known to be breeding on their own, will not be a part of the sanctuary, but will be left in the wild and protected by anti-poaching units.

The sanctuary already has its first resident. It is, of course, none other than Tam, who is bidding his time until the new sanctuary is built and the other rhinos are caught and brought in. If all goes according to plan Tam will come face-to-face with a female, perhaps his first ever. Payne says that the sanctuary only needs one more male and two females to make the program “just about doable”.

The plan has received full-support by the government and funds have been promised to the tune of 8 million ringgits by the national government (over 2 million US dollars) and 250,000 ringgits (70,000 US) by the State Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Environment for interim holding paddocks for rhinos. The sanctuary has also received a large donation by the Sime Darby Foundation, a corporate social and environmental responsibility arm of one of Malaysia’s largest palm oil companies. All that needs to happen now is implementation on the ground: basic infrastructure is scheduled to be completed by next year.

“Director of Sabah Forestry Department, Datuk Sam Mannan, and Sabah Minister of Tourism, Culture and Environment, Datuk Masidi Manjun have both taken lead roles in supporting the early stages of the program, and both have shown a strong personal interest in pushing it forward.” said Payne.

Masidi, well-known is Sabah for his unwavering commitment to environmental issues, headlined a fundraiser in the spring organized by LEAP that raised 530,000 ringgits (150,000 US) for BORA. Without such government support, the plan to save the rhinos would have stalled before it even started.

Payne believes that Sabah is the best hope for the Sumatran rhino going forward, despite Indonesia having a larger population of the rhinos.

“Due to human population pressures in Indonesia and the massive expansion of big scale plantations that compete for land with small-holders,” Payne says that “it may be only a matter of time before the Sumatran rhino vanishes from the wild in Indonesia”.

A large number of unanswered questions remain—such as just how many rhinos are left and how many are capable of breeding—but Payne says that the answer to these questions are largely unnecessary for conservation efforts.

“What is the point spending 10 years researching if the population is 10 or 15 individuals when the species is still going down?” he asked.

Conservation, according to Payne, cannot always wait for hard science and data; often it comes down to using one’s “best judgment” at the time to save a species.

When I left Tam the first time, I thought it would be the last. But the next morning, to my surprise, we were able to visit him again. Beforehand we followed rangers with the Sabah Wildlife Department in a pick-up as they cut branches, leaves, and vines for Tam’s breakfast.

By the time we reached Tam, he was already waiting at the gate where they feed him, rubbing his head against the bars. Tam was “like a cat rubbing against you”, Cynthia Ong had told me, and it was true. He would rub his head along the bars like a pet asking for attention. In fact, he had largely rubbed away his magnificent horn. This shouldn’t be seen as a bad thing: without a horn he is of little interest to poachers.

Ong described the day that Tam wandered injured into the palm oil plantation as a “fortuitous and unplanned event”, because “it pushed the idea of [the] proposal” to start a massive rhino sanctuary.

Tam, she told me, “is not an accident”.

After eating his breakfast—carefully measured out on a scale meant for a giant—and having his photo taken a few hundred times, Tam turned and made his way back into the forest. First, he spent a moment wading in the mud and then slowly, but surely, he wandered back into the deep green of Borneo’s jungle. One moment he was there, roaming on the forest’s edge and the next he was gone as if he had never been.

Days before when I asked Junaidi Payne if this was the last chance to save the species, he told me simply: “Yes.”

It’s true that this story will end in one of two ways. In the first Tam and all of his kind will vanish from the dwindled forest, leaving not even their ghosts behind. In this version, he will become another member of those animals painted so nicely in books on extinction: Tam, I imagine, will appear somewhere between the dodo, the thylacine, and the great auk.

In the second version Tam and his kind will continue inhabiting the deep, largely unseen areas of Southeast Asia’s magnificent forests. While this version is dependent on many factors not in our control—factors where previous generations have already failed the rhino—it is our choice now whether or not we give this ending a chance.

I don’t know what we will find when the last page is turned, but having been among the fortunate few to come face-to-face with the two-horned rhino of Asia, I can’t help but dread the day we fail, while simultaneously hoping for the day where I can take my children to meet Tam’s.

____________________________________________________

This article written by Jeremy Hance was originally published on MONGABAY.COM

Mongabay.com seeks to raise interest in and appreciation of wild lands and wildlife, while examining the impact of emerging trends in climate, technology, economics, and finance on conservation and development.

Visit Mongabay to read the original article and others like it.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- Next Page »